Partial molar property

A partial molar property is a thermodynamic quantity which indicates how an extensive property of a solution or mixture varies with changes in the molar composition of the mixture at constant temperature and pressure, or for constant values of the natural variables of the extensive property considered. Essentially it is the partial derivative with respect to the quantity (number of moles) of the component of interest. Every extensive property of a mixture has a corresponding partial molar property.

Contents |

Definition

The partial molar volume is broadly understood as the contribution that a component of a mixture makes to the overall volume of the solution. However, there is rather more to it than this:

When one mole of water is added to a large volume of water at 25 ºC, the volume increases by 18 cm3. The molar volume of pure water would thus be reported as 18 cm3 mol-1. However, addition of one mole of water to a large volume of pure ethanol results in an increase in volume of only 14 cm3. The reason that the increase is different is that the volume occupied by a given number of water molecules depends upon the identity of the surrounding molecules. The value 14 cm3 is said to be the partial molar volume of water in ethanol.

In general, the partial molar volume of a substance X in a mixture is the change in volume per mole of X added to the mixture.

The partial molar volumes of the components of a mixture vary with the composition of the mixture, because the environment of the molecules in the mixture changes with the composition. It is the changing molecular environment (and the consequent alteration of the interactions between molecules) that results in the thermodynamic properties of a mixture changing as its composition is altered

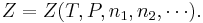

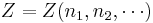

If, by  , one denotes a generic extensive property of a mixture, it will always be true that it depends on the pressure (

, one denotes a generic extensive property of a mixture, it will always be true that it depends on the pressure ( ), temperature (

), temperature ( ), and the amount of each component of the mixture (measured in moles, n). For a mixture with m components, this is expressed as

), and the amount of each component of the mixture (measured in moles, n). For a mixture with m components, this is expressed as

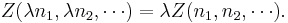

Now if temperature T and pressure P are held constant,  is a homogeneous function of degree 1, since doubling the quantities of each component in the mixture will double

is a homogeneous function of degree 1, since doubling the quantities of each component in the mixture will double  . More generally, for any

. More generally, for any  :

:

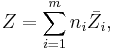

By Euler's first theorem for homogeneous functions, this implies

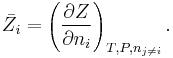

where  is the partial molar

is the partial molar  of component

of component  defined as:

defined as:

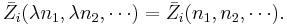

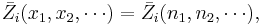

By Euler's second theorem for homogeneous functions,  is a homogeneous function of degree 0 which means that for any

is a homogeneous function of degree 0 which means that for any  :

:

In particular, taking  where

where  , one has

, one has

where  is the concentration, or mole fraction of component

is the concentration, or mole fraction of component  . Since the molar fractions satisfy the relation

. Since the molar fractions satisfy the relation

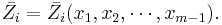

the xi are not independent, and the partial molar property is a function of only  mole fractions:

mole fractions:

The partial molar property is thus an intensive property - it does not depend on the size of the system.

Applications

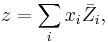

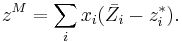

Partial molar properties are useful because chemical mixtures are often maintained at constant temperature and pressure and under these conditions, the value of any extensive property can be obtained from its partial molar property. They are especially useful when considering specific properties of pure substances (that is, properties of one mole of pure substance) and properties of mixing. By definition, properties of mixing are related to those of the pure substance by:

Here  denotes the pure substance,

denotes the pure substance,  the mixing property, and

the mixing property, and  corresponds to the specific property under consideration. From the definition of partial molar properties,

corresponds to the specific property under consideration. From the definition of partial molar properties,

substitution yields:

So from knowledge of the partial molar properties, properties of mixing can be calculated.

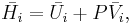

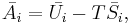

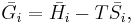

Relationship to thermodynamic potentials

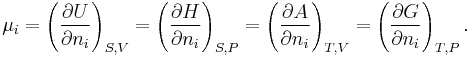

Partial molar properties satisfy relations analogous to those of the extensive properties. For the internal energy U, enthalpy H, Helmholtz free energy A, and Gibbs free energy G, the following hold:

where  is the pressure,

is the pressure,  the volume,

the volume,  the temperature, and

the temperature, and  the entropy.

the entropy.

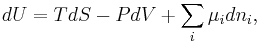

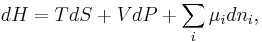

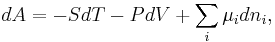

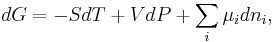

Differential form of the thermodynamic potentials

The thermodynamic potentials also satisfy

where  is the chemical potential defined as (for constant nj with j≠i):

is the chemical potential defined as (for constant nj with j≠i):

This last partial derivative is the same as  , the partial molar Gibbs free energy. This means that the partial molar Gibbs free energy and the chemical potential, one of the most important properties in thermodynamics and chemistry, are the same quantity. Under isobaric (constant P) and isothermal (constant T ) conditions, knowledge of the chemical potentials,

, the partial molar Gibbs free energy. This means that the partial molar Gibbs free energy and the chemical potential, one of the most important properties in thermodynamics and chemistry, are the same quantity. Under isobaric (constant P) and isothermal (constant T ) conditions, knowledge of the chemical potentials,  , yields every property of the mixture as they completely determine the Gibbs free energy.

, yields every property of the mixture as they completely determine the Gibbs free energy.

Calculating partial molar properties

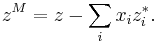

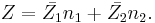

To calculate the partial molar property  of a binary solution, one begins with the pure component denoted as

of a binary solution, one begins with the pure component denoted as  and, keeping the temperature and pressure constant during the entire process, add small quantities of component

and, keeping the temperature and pressure constant during the entire process, add small quantities of component  ; measuring

; measuring  after each addition. After sampling the compositions of interest one can fit a curve to the experimental data. This function will be

after each addition. After sampling the compositions of interest one can fit a curve to the experimental data. This function will be  . Differentiating with respect to

. Differentiating with respect to  will give

will give  .

.  is then obtained from the relation:

is then obtained from the relation:

See also

Further reading

- P. Atkins and J. de Paula, "Atkins' Physical Chemistry" (8th edition, Freeman 2006), chap.5

- T. Engel and P. Reid, "Physical Chemistry" (Pearson Benjamin-Cummings 2006), p.210

- K.J. Laidler and J.H. Meiser, "Physical Chemistry" (Benjamin-Cummings 1982), p.184-189

- P. Rock, "Chemical Thermodynamics" (MacMillan 1969), chap.9

External links

- Lecture notes from the University of Arizona detailing mixtures, partial molar quantities, and ideal solutions